Non-Xmas

As the hardwoods shed the blushing leaves of fall, sapped of sun and shorn—there, naked among the evergreens and ivy—we are exposed to wintertime snaps and freezing naps. Rigid, frigid forms reach longingly into the silver clouds of dawn. From a distance, frayed branch-bristles paint the sun into the sky; a fulgid effulgence and welcome respite from the umbral evening's bleak breadth. The verdant branches of vernal days have passed; their merciful shade now gives way to gray skies.

The irony here is obvious. We spend the whole year cutting down trees, only to bring some indoors for a short while. That is, assuming they’re not artificial trees. Nowadays, it seems to be the normative—and, some have argued, the more sustainable—option to have a fake tree. That is, supposing you don't throw it away and buy a new one each year (Hardt 2022). Relatively recently, it appears that renting Christmas trees has become an option for some (Mehta 2021). Whatever your stance, pleasure, or proclivities when it comes to economics, sustainability, tradition, it seems like there’s a tree out there for you.

But what does this desire to have (sometimes fake) trees in the first place, bedighting places of work, worship, commerce, and respite reveal about the pervasive fixity of these traditions—those whose origins we cannot quite place or explain with any sound logic, other than the fact that many of us remember Christmases of years' past, associate warm and happy memories with them, and wish to, on some level, recreate the hygge of the holiday season? Just musing here—I have no intention of going into an in-depth history of Christmas trees, nor their religious, spiritual, or semiotic contents at considerable length. In proper geographic fashion, I’m more interested in “the why of where.” But perhaps this is more of a humanist geographic tangent, as I'm also deeply curious about who creates the “whys,” and of what these whys are apropos.

My home state has one such interesting “why.” With one of the most prolific Christmas tree industries in the Southeastern United States, the state of North Carolina has done well to keep these memories alive—and, ostensibly, create new ones. The numbers are quite staggering, with 5-6 million trees harvested annually—the vast majority of which being a native evergreen species, the Fraser fir (Owen 2016). This industry is also rather lucrative, with a retail value of around $25 million (Owen 2016). After Hurricane Helene rocked, flooded, and shocked the mountains of North Carolina in 2024, this Christmas tree industry did not go unscathed (Quillin 2025).

It is also worth mentioning that, consistent with much of North Carolina’s agricultural industries, many of these vast nurseries rely on the care of migrant labor (Contreras and Griffith 2011). And it can take years for these trees to grow to marketable heights. A tree isn't just a tree; it's everything—and everyone—that went into it; the hands and sweat and blood and tears of the people who may have no choice but to subsist on Yuletide whimsy. Every needle and frond is bred and trimmed to the tastes of consumers who value, among other things, the sacred deracination of an organic life form—one which was grown and groomed to die. It is not uncommon to adorn these arboreal corpses with baubles, tinsel, tiny lights, and all manner of magpie-like assemblages of festive accouterments. The trees are trimmed to our liking, in the image of the mental surrogate that sweetens some ideal image of the Christmas tree; not just a Christmas tree.

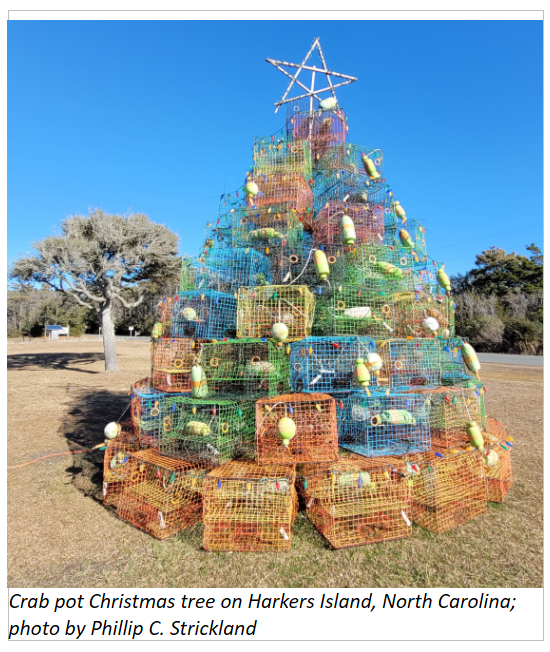

Some people also deck the halls with wreaths, mistletoe, and poinsettias. Some resort to using native vegetation as their canvas; I’ve seen places where a palm tree or potted succulent will suffice. Where I grew up, on North Carolina’s Coastal Plain, crab pot Christmas trees were not uncommon. And, where there are those who have neither the heart, time, or taste to pluck a plant from the earth, a faux tree will do—no water, no needles, no pine-scented atmosphere—unless you want that of course, in which case you can buy a pine scent in a can. What will we come up with next?

Intuitively, as with other domains (food, clothing, and pornography, for example), we understand that there are certain tradeoffs and benefits to seeking the synthetic over “the real thing.” Some can do without—and, indeed, appreciate—the absence of some of these features. But, for those with more particular appetites, capitalism has trickled in, forming rivulets in the furrows of desire. One may want a plastic tree (because they require less maintenance), but would sorely miss the pine-scented Christmas mornings of her youth. For her, Christmas would not be Christmas without the smells of the season—as well as its tastes and sights. Lo and behold, she can buy her Christmas in cans. Christmas is portable, modifiable, open source, and open-ended. Depending on your flavor of Christianity, you might observe various Christmas extensions—or “Christmastide”—like Advent, Epiphany, Saint Nicholas Day, Saint Knut’s Day, and the Twelve Days of Christmas (yes, it’s actually a thing, although, in my experience, there are fewer birds than you might expect, golden rings, and maids a-milking [what were those maids supposed to be a-milking, anyway?]). There’s also the Feast of Adam and Eve, which was commonly celebrated in Germany—and gives us some of the most solid, early examples of what we would now recognize as a Christmas tree (Britannica Editors 2025).

Emotions run high during the holidays; moments of intense jubilation contrasted with the smoldering silence brought on by the passive-aggressive slights of your kin. Good. Evil. Suddenly, these things seem clearer in the cold, stark air; so far away from Eden, yet content to taste the nectar we’re said to have Fallen for.

And so, Eden stretches out. The holiday blankets and adorns of the landscape; bows and garlands are strewn about while familiar earworms hang in the air. It’s like some nagging, intracranial pine-scented residue. Nutcrackers and peppermint swirls; candy canes and mincemeat pies. Gingerbread houses. The people you spent this time with “as in olden days, happy golden days of yore.” Holly and wee ivy wind around our world, intruding upon even the most liminal of spaces and—in a strange way—fostering a heightened sense of liminality itself. Cliches decorated with cliches.

Here, my definition of “liminality” is a kind of pseudo-academic blunt object, haphazardly welding Victor Turner to the more recent aesthetic phenomenon which has seized and choked the Internet like a lusty dust bowl. What a world we live in, decorating our non-places...

A world where people are born in the clinic and die in hospital, where transit points and temporary abodes are proliferating under luxurious or inhuman conditions (hotel chains and squats, holiday clubs and refugee camps, shantytowns threatened with demolition or doomed to festering longevity); where a dense network of means of transport which are also inhabited spaces is developing; where the habitue of supermarkets, slot machines and credit cards communicates wordlessly, through gestures, with an abstract, unmediated commerce; a world thus surrendered to solitary individuality, to the fleeting, the temporary and ephemeral...It never exists in pure form; places reconstitute themselves in it; relations are restored and resumed in it; the 'millennial ruses' of 'the invention of the everyday' and 'the arts of doing.’ (Augé 1995, 78-79).

Marc Augé (1995) describes non-places as, essentially, those locations which are the products of what he calls "supermodernity;" that is, an age which is characterized by rampant industrialization, technological advancement, and, perhaps most importantly, commercialism. But as neoliberal paradigms continue to bleed into every crevice of commercial existence, filling in the gaps and constituting the coalescence of “place,” “non-place,” “space,” and even “cyberspace,” it begins to feel more and more to me that anywhere could potentially be a non-place, and a place (either virtual or in real life) at the same time, depending on who is “there.”

Today, Christmas can be seen as the festive manifestation of supermodernity par excellence. Almost anyone and everyone can buy into it—if not religiously, then culturally; if not culturally, then commercially; if not commercially, then ironically. How many non-places can you spot in popular holiday films? In real life? Airports, hotel rooms, train stations, hotel lobbies, and now—as one of my favorite channels on YouTube, Retail Archaeology (2025), has made abundantly clear—malls. What is it about these non-places that remind us of the holidays? Perhaps the emptiness in the midst of abundance creates an eye in the storm of capitalism; a liminal period of reflection in the stillness of winter; an annual resolution after the climax of consumption; a cold, comfortable burnout. A death. Now that I think about it, all of the best Christmas stories are about death. It is even said that the iconic Nativity foreshadows the fate of Jesus and the Eucharist; the Messiah born in a manger, given gifts more befitting of a mournful, funerary occasion.

Of course, the particulars of even this myth are contested by some. I am reminded by an evocative vignette from Zora Neale Hurston's (2009) Tell My Horse.

I witnessed a wonderful ceremony with candles. I asked Brother Levi why this ceremony and he said, “We hold candle march after Joseph. Joseph came from cave where Christ was born in the manger with a candle. He was walking before Mary and her baby. You know Christ was not born in the manger. Mary and Joseph were too afraid for that. He was born in a cave and He never came out until He was six months old. The three wise men see the star but they can’t find Him because He is hid in cave. When they can’t find Him after six months, they make a magic ceremony and the angel come tell Joseph the men wanted to see Him. That day was called ‘Christ must day’ because it means ‘Christ must find today,’ so we have Christmas day, but the majority of people are ignorant. They think Him born that day. (Hurston 2008, 4).

This folk etymology of "Christmas," of course, is not the consensus view among academic historians and philologists. But the spiritual truth behind this etymology is genuine and true to the ethos of the holiday—at least, inasmuch as this could be considered copacetic with the contemporary Christian diaspora. In a time where coloniality continuously engraves the doctrines of neoliberal logic into the flesh of the world, Christmas, too, is brokered and reinscribed; translated and articulated in phenomenal ways to meet the cadence of cultural flux. Decorations are a part of this ongoing process, and they are signs of what I like to call a “War of Christmas,” a pithy retort (even if I do say so myself) to the so-called “War on Christmas.”

Even in pre-Christian times, the celebrations of Yule, the Kalends, Saturnalia, and Dies Natalis Solis Invicti ("the Birthday of the Unconquered Sun") used verdant or floral decorations; things that evoke the sacred endurance of biological life.

But again, all the best Christmas stories are—on the face of it—about death (or, at the very least, the evanescence of life). Let's make no mistake; the bleak midwinter is a death march for festive evergreens. So, what do we do with our little green corpses, these reminders of warmth in a freezer-burned world? We set them ablaze. Sometimes with fire, sometimes with LED lights.

Christmas, in its post-Dickensian hypermodern formulation is, in my view, the ultimate test of the influence of neoliberalism. Granted, I am no economist or political philosopher. But what are some of the anthropological elements of Christmas? Well, we can take this back to Marcell Mauss, where gift-giving and reciprocity forms the backbone of all economic activity. And we also have kinship; being with the people you love and care for the most (at least, in theory). Even though, strictly speaking, Christmas is just a culturally salient mechanism of worldwide neoliberal capitalist expansion which only serves to stimulate international commerce under the guise of an intrinsically sacred winter festival. “Humbug.”

Maybe all forms of gift-giving are shams fraught with ulterior motives and peripheral prerogatives. But whither altruism—the kind that suitably corroborates the aura of the holiday season? Despite ourselves, even if we acknowledge the structures, institutions, and economic functions of Christmas—its reliance on exploitation, corporate greed, materialism, and even the proclamations of a "War on Christmas," (as war can be profitable, too; Christians seeing fit to mobilize their victim complexes) many of us manage to bite around these lumps of coal. In any case, such winter festivals make great use of myth-making itself. But I like to think they are myths to live by—good will, peace on Earth, and all that warm, fuzzy stuff. Hold on to it if you can. It might be all you have left when all other avenues of common decency and welfare have come up cold, dead, and dry as that harsh desert: the days of winter.

Social scientists and philosophers (many who are much smarter and more experienced than I am) maintain the privilege to consider how, exactly, these elements coalesce. As a whole, conceding the elements of global hegemony, ties to coloniality, and supermodernity—understanding, likewise, that there are many who truly embrace the altruistic spirit of gift-giving—it would be unfair to say that we could not, in good conscience, celebrate the holiday at all, even as we critically examine it. I certainly do, as I have places to go, people to see, and non-places to pass through; the non-places have their places. Window shopping lacks a certain charm without window dressing. But what happens when the window dressing is all we’re able to consume; feast our eyes on the evergreens and lights; reminding us that it’s the “most wonderful time of the year,” when the shiny things behind the glass might as well be locked away in the Louvre?

There’s no place like home for the holidays…no space like a place for the holidays.

I hope you all have a place.

-BIBLIOGRAPHY-

Archaeology, Retail, dir. 2025. A Dead Mall Christmas | Retail Archaeology. Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9EaTDcqsjUY.

Augé, Marc. 1995. Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. Verso.

Boyd, Rachel. 2022. “‘Recycling, Repurposing and Saving Nature’: Old Christmas Trees Fight Erosion.” Spectrum Local News, January 12. https://spectrumlocalnews.com/nc/charlotte/news/2022/01/12/christmas-tree-dune-restoration.

Britannica Editors. "Christmas tree." Encyclopedia Britannica, December 16, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/plant/Christmas-tree.

Contreras, Ricardo, and David Griffith. 2011. “BUILDING A LATINO‐ENGAGED ACTION‐RESEARCH COLLABORATIVE: A CHALLENGING UNIVERSITY–COMMUNITY ENCOUNTER.” Annals of Anthropological Practice 35 (2): 96–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2153-9588.2011.01084.x.

Hardt, Braelei. 2022. “Are Real or Fake Christmas Trees Better for the Environment?” The National Wildlife Federation Blog, November 29. https://blog.nwf.org/2022/11/are-real-or-fake-christmas-trees-better-for-the-environment/.

Hurston, Zora Neale. 2008. Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica. HarperCollins e-books.

Mehta, Shreshthi. 2021. The Living Christmas Company: Making Christmas Merry for Trees. SAGE Publications: SAGE Business Cases Originals. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529751918.

Miller, Daniel. 2017. “Christmas: An Anthropological Lens.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 7 (3): 409–42. https://doi.org/10.14318/hau7.3.027.